Recently I wrote the YA version of one of Jared Diamond’s books. It was the first long project I’d begun in Scrivener. I’d imported a couple of WIPs into Scrivener, but starting a manuscript from the ground up in the program gave me new insights into its usefulness.

I also made a Scrivener mistake I’ll never make again.

Today I’m passing on three tips–which are really appreciations of Scrivener features I found especially handy–and a warning against that dumb mistake.

First, some context. Writers of all kinds use Scrivener, but most articles I’ve seen are aimed at novelists. I too use Scrivener to write fiction, but my paying gig is writing nonfiction books, mostly YA. In addition to my own books for various publishers, I’ve adapted a handful of science and history bestsellers into YA versions. (The best-known of these is probably The Young People’s History of the United States, an adaptation of Howard Zinn’s monumental progressive history.)

For years I’ve worked in Word (since 2007, in OpenOffice’s clone of Word). I’m expected to turn my mss. in to my publishers as .doc files. Scrivener makes it very easy to export into a .doc file. I doubt I’ll ever again embark on a nonfiction project–or any writing project longer than a couple of pages–in anything but Scrivener.

If you’re reading this, you probably already know something about Scrivener. If you don’t, go on over to the developer’s website, www.literatureandlatte.com, and check out this feature-rich, flexible writing software for Windows and Mac. I’m not trying to introduce you to Scrivener or describe it in detail, just to share a few things I’ve learned.

They are:

1. Embrace the binder.

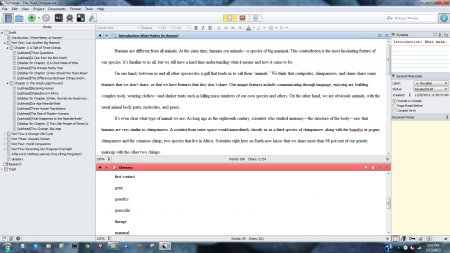

The binder is the vertical panel at the left of the Scrivener workspace. It contains a folder for each part of the project, organized into files as needed. This was, in essence, the outline I showed to the publisher and Professor Diamond before I started the writing. (Click on the image to embiggen.)

For the YA version of The Third Chimpanzee, I didn’t have to do research or create a structure. The parent text–Diamond’s book–was my source. Like the parent text, my manuscript would consist of an Introduction, five Parts (each with a one- or two-page opener, summing up what that Part would cover), and an Afterword. In the parent text, each Part had from two to five chapters. With a few exceptions, which I’ll mention in a moment, I followed that pattern.

But I did have to break the chapters down into sections and create many, many subheads–standard in YA nonfiction–for those sections. I also had to pull elements from the parent text out into sidebars. The outline I developed in Scrivener’s binder showed all of the subheads and sidebars for each chapter.

Those exceptions I mentioned? In a few places I diverged from the structure of the parent text. While still in the outline stage I combined three chapters on human sexuality into one. (Even one can raise the alarm for school-board Grundys.) Later, during the writing, I cut, rearranged, or combined a few sections. I even cut an entire chapter. The binder made it easy to enact these changes. Deleting is always easy, of course. Maybe too easy. Before every cut, I used Scrivener’s Snapshot feature to preserve the current version. As for combining and rearranging, just drag-and-drop the binder entry, and the corresponding text travels with it in the document. While working I usually collapsed all of the Parts folders except the one with the chapter I was writing.

2. Write out of order.

Sometimes I write a book straight through from the beginning to the end. Sometimes I write the first and last chapters, then fill in the middle. Sometimes I write all the sidebars first. No matter how I write, I have always preferred to work with one long (sometimes very long) .doc file instead of separate files for each chapter. Most of the time the back matter–glossary, timeline, biblio, etc.–is also in that same file, at the end. It’s what I’m used to. But it can mean a lot of scrolling ahead and back.

For the Third Chimp adaptation, my goal was to use as much of Professor Diamond’s original text as possible, cutting and simplifying and adding information to make it accessible to younger readers, rewriting only when necessary. As always when doing these adaptations, I want to preserve the author’s voice and tone.

To feel my way into The Third Chimp, I chose to begin by writing the Intro, the Afterword, and the five Part openings. With those in place, I felt I’d established a consistent tone. (And I always like knowing, as I work my way through the guts of a ms., that the last bit is already written.) I then wrote the chapters for Part One, Part Four, Part Five, Part Three, and Part Two in that order.

Never had it been so easy to write a long (50+K) manuscript nonconsecutively! No scrolling needed, just a click on the binder entry and boom, there I was. And I could see at a glance which chapters, sections, and sidebars remained to be done–Scrivener fills in the small file or folder icon in the binder entry when you’ve written some text for it.

3. Use the split screen.

One of my tasks was to build a glossary for the YA version of The Third Chimp. For me, the best way to do this is to compile a list of potential glossary terms as I work, then write the definitions after the ms. is complete. In Word, I occasionally I kept the glossary list in a separate file and flipped into it every time I wanted to add a term (or check to see if it was already listed). More often, though, the glossary was part of the back matter at the end of the long single file, and I had to scroll back and forth between it and what I’d been writing. Tedious.

With Scrivener’s split screen, as you can see, I opened my glossary list in the bottom window of the text editor. The top window held the section I was writing. This saved a lot of time and aggravation. I didn’t always keep the glossary open, but when I needed it, it was right there.

And now for that warning:

Avoid premature exportation.

You know how it is when you’re writing, especially a long text. You get restless, you start looking for things to do that aren’t writing but are kinda writing-related, so you can use them to justify not writing. Usually for me it’s “more research.” But except for a few minor updates, I didn’t have to research The Third Chimp; Professor Diamond had done that.

So one day, somewhere past the midpoint of writing the book, but not nearly close enough to the end, I got to thinking about that end. I would have to present a .doc file to the publisher and Professor Diamond for their review. Maybe I should give Scrivener’s Compile and Export features a test run?

Compile is a powerful command that can do many subtle things. But with no front or back matter involved, my Compile was pretty simple: just assemble all the text units, with page breaks at the end of each Part or Chapter. A couple of clicks later I had a .doc file in 12-pt. Times New Roman, double-spaced.

I should have stopped right there, curiosity satisfied, and deleted that file and gone back to Scrivener to finish my book.

But I noticed something wrong, something that had bugged me with each new section I wrote in Scrivener. I use a standard paragraph indent for every para EXCEPT the first para after any title: Part, Chapter, Section, Sidebar. Those first paras only have to be flush left. I could never figure out how to tell Scrivener that. It indented all my paragraphs.

Without thinking, I started idly scrolling through the newly created .doc file of my three-fifths complete manuscript, left-flushing all those first paragraphs. It took a while. Along the way I saw typos, infelicitous word choices, and clunky sentences, and fixed them. Why? Maybe I was lulled or seduced by the familiarity of the Word-clone interface–I’d written more than a hundred books in it.

At any rate, by the time I realized I’d been editing the unfinished ms. outside Scrivener, I decided, rightly or wrongly, that it was too late to move it all back in. I’d keep the changes I’d made and simply write the remaining two-fifths of the book in OpenOffice.

Reader, I wrote it. And it will soon be published by Triangle Square Books, an imprint of Seven Stories Press. But writing the last two-fifths was a lot less convenient than writing the first three-fifths.

Ditch Scrivener in mid-project? Learn from my mistake. Don’t do that.

ies Press has just released my YA adaptation of his book 1493, which explores what happened to crops, climate, wildlife, and people when the first worldwide network of trade and travel got started in the sixteenth century. From Chinese pirates to South American freedom fighters to the man who convinced the king and queen of France to wear potato flowers, Mann’s book is filled with the stories of individuals who shaped and were shaped by history.

ies Press has just released my YA adaptation of his book 1493, which explores what happened to crops, climate, wildlife, and people when the first worldwide network of trade and travel got started in the sixteenth century. From Chinese pirates to South American freedom fighters to the man who convinced the king and queen of France to wear potato flowers, Mann’s book is filled with the stories of individuals who shaped and were shaped by history.