Zachary’s in Italy for a couple of weeks. At such times I enjoy taking on projects: sorting out the hall closet, say, or organizing the pantry. This time I’ve inventoried my fiction output.

Two realizations led me to spend the last couple of hours sorting files, an enterprise that eventually required me to fire up Z’s oldest, most dust-covered computer.

One realization was that I want to use Scrivener for writing and revising fiction from now on. To this end I consolidated all the files for current or recent stories and novels from my laptop and netbook into one set of files with a consistent labeling system. The next step will be to decide what’s worth working on, prioritize it, and import those files into Scrivener.

The other realization was that there was a shocking amount of stuff–from mss. of romance novels that were published in the 90s to proposals, ideas, and correspondence–languishing on 3.5-inch floppies in a box in my office. Hence the firing up of the aforementioned ancient computer, the copying of files from many floppies onto a flash drive, and the examination of those files on my laptop.

They were full of surprises related to my nonfiction career and to fiction projects I’d started but set aside long ago. In addition to the usual kind of thing–letters I don’t remember writing to people I don’t remember meeting–I found that I have full mss. (some in WordPerfect 4.2! but OpenOffice converted it) of successful nonfic books from decades ago. That got me thinking about self-pubbing some of them, now that rights have reverted, on the “nothing to lose” principle.

On the fiction front, I found proposals and ideas for romance novels from back when I was writing for Harlequin. Some that got turned down then as too weird or unconventional would seem tame in today’s romance market. I also rediscovered a fat Civil War novel I ghost-wrote for a CEO in the 1980s; the surprise here was how little I got paid for it, although I must’ve thought it was enough at the time.

The best part was that while copying the files for a historical novel I started a long time ago, but gave up on after 105 pages, I got an idea for turning it into a steampunk novella, so now I can be excited about it all over again.

After all this filing, an afternoon of yard work might be positively refreshing. But probably not.

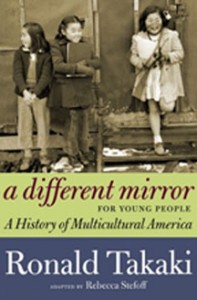

launch of Triangle Square Books, a new children’s and YA nonfiction imprint from Seven Stories Press.

launch of Triangle Square Books, a new children’s and YA nonfiction imprint from Seven Stories Press.

The big stump was there when we arrived. There was one twice as big just across the road.

The big stump was there when we arrived. There was one twice as big just across the road.